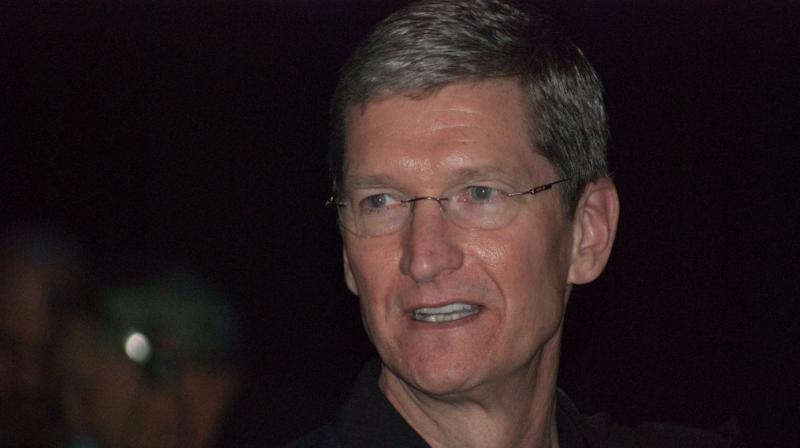

But it hasn’t always been easy. Among the challenges Cook has faced: a slowdown in iPhone sales as smartphones matured, a showdown with the FBI over user privacy, a US trade war with China that threatened to force up iPhone prices and now a pandemic that has closed many of Apple’s retail stores and sunk the economy into a deep recession.

Cook, 59, has also struck out in into novel territory. Apple now pays a quarterly dividend, a step Jobs resisted partly because he associated shareholder payments with stodgy companies that were past their prime. Cook also used his powerful perch to become an outspoken advocate for civil rights and renewable energy, and on a personal level came out as the first openly gay CEO of a Fortune 500 company in 2014.

Apple declined to make Cook available for an interview. But it did point to 2009 comments Cook made to financial analysts when he was running the company while Jobs battled pancreatic cancer.

Asked what the company might look like under his management, Cook said that Apple needs “to own and control the primary technologies behind the products we make.” It has doubled down on that commitment, becoming a major chip producer in order to supply both iPhones and Macs. He added that Apple would resist exploring most projects “so that we can really focus on the few that are truly important and meaningful to us.”

That laser focus has served Apple well. At the same time, though, under Cook’s stewardship, Apple has largely failed to come up with breakthrough successors to the iPhone. Its smartwatch and wireless ear buds have emerged as market leaders, but not game changers.

Cook and other executives have dropped hints that Apple wants make a big splash in the field of augmented reality, which uses phone screens or high-tech eyewear to paint digital images into the real world. Apple has yet to deliver, although neither have other companies that have hyped the technology.

Apple also remains a laggard in artificial intelligence, particularly in the increasingly important market for voice-activated digital assistants. Although Apple’s Siri is widely used on Apple devices, Amazon’s Alexa and Google’s digital assistant have made major inroads in helping people manage their lives, particularly in homes and offices.

Apple also has stumbled a few times under Cook’s leadership.

In 2017, it alienated customers by deliberately but quietly slowing the performance of older iPhones via a software update, ostensibly to spare the life of aging batteries. Many consumers, though, viewed it as a ploy to boost sales of newer and more expensive iPhones. Amid the furor, Apple offered to replace aging batteries at a steep discount; later it paid $500 million to settle a class-action lawsuit over the matter.

Apple has also faced government investigations into its aggressive efforts to minimize its corporate taxes and complaints that it has abused control of its app store to charge excessive fees and stifle competition to its own digital services. On the tax front, a court ruled in July that Apple did nothing wrong.

Cook has turned the app store into the cornerstone of a services division that he set out to expand four years ago. At the time, it was growing clear that sales of the iPhone—Apple’s biggest money maker—were destined to slow down as innovations grew sparse and consumers kept their old devices for longer.

To help offset that trend, Cook began to emphasize recurring revenue from app commission, warranty programs and streaming subscriptions to music, video, games and news sold for the more 1.5 billion devices already running on the company’s software.

Apple’s services division now generates $50 billion in annual revenue, more than all but 65 companies in the Fortune 500. Ives estimates Apple’s services division by itself is worth about $750 billion—about the same as Facebook currently is in its entirety.

That division could be worth even more now had Cook done something many analysts believe Apple should have done at least five years ago by dipping into a hoard of cash that at one point surpassed $260 billion to buy Netflix or a major movie studio to fuel its video streaming ambitions.

Buying Netflix seemed like within the realm of possibility five years ago when the video streaming service was valued at around $40 billion. Now that Netflix is worth more than $200 billion today, that idea seems off the table, even for a company with Apple’s vast resources.